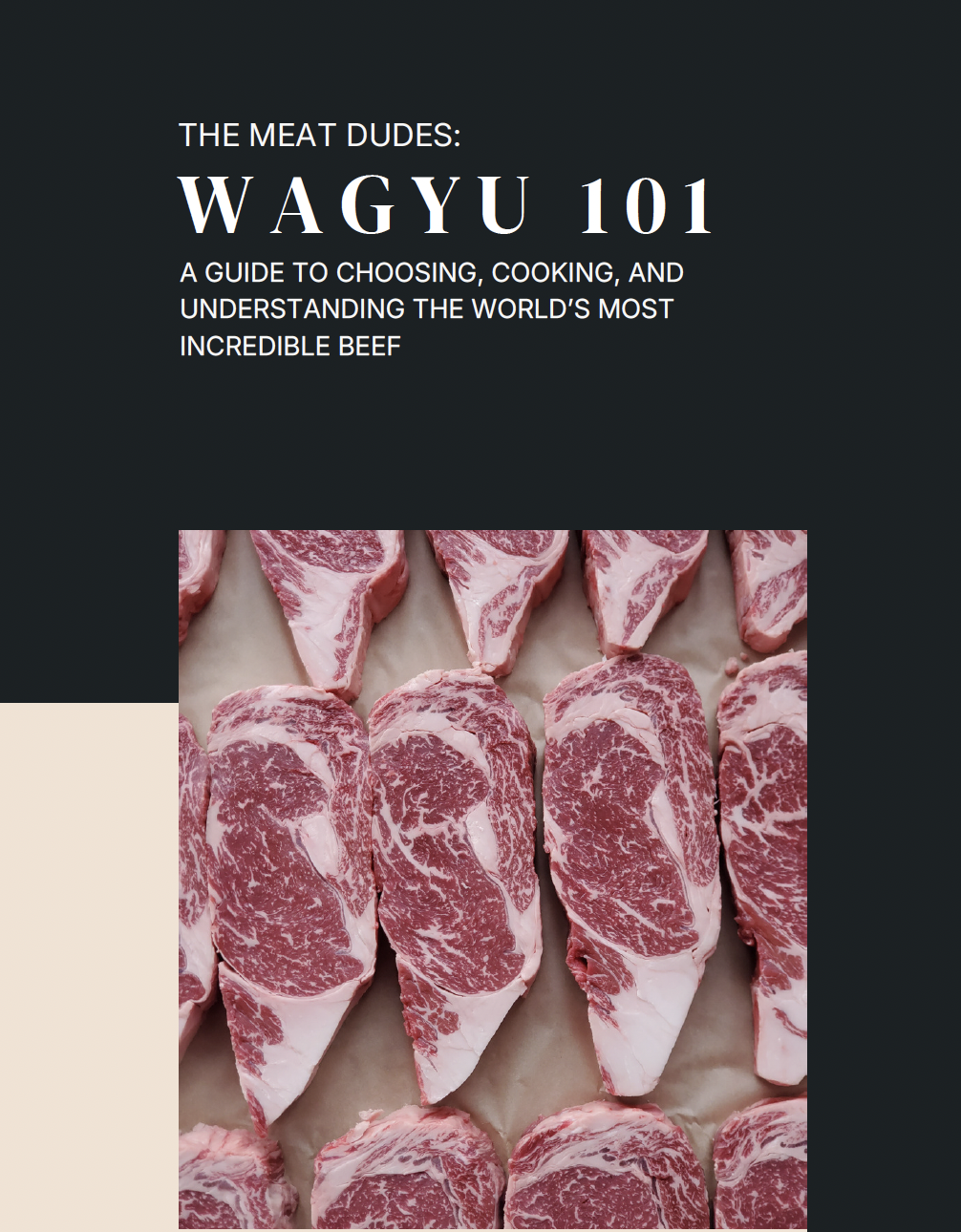

When you hear “Wagyu,” you likely think of thin-sliced Japanese A5 beef, the ultra-decadent steaks with crazy marbling that melt on your tongue. But here’s the truth: American Wagyu isn’t trying to be Japanese A5 — and that’s exactly why it deserves its own place on your plate. American Wagyu brings its own value, flavor profile, scale and style.

The term American Wagyu covers a wide spectrum: from F1 crosses (50% Wagyu genetics) to purebred (93 %+ Wagyu), and even full blood (100 % Wagyu genetics, traceable to Japan) raised in the U.S. Each of these has a unique flavor, texture and scale of production. Understanding those differences helps when you’re picking a steak, a burger or a special meal. And that’s why talking about “what American Wagyu is” matters.

One key thing: the American consumer wants a steak—think 12-16 oz, charred exterior, red center—not a few thin slices of melt-away beef. Japanese A5 is often enjoyed in smaller portions due to its intense fat content, higher cost and different eating culture. So when you buy American Wagyu, you’re getting a hybrid of luxury and practicality: great genetics, rich marbling, but built for the grill sessions, steak nights and everyday indulgence.

What Builds American Wagyu: Genetics, Terroir & Scale

Genetics. One major difference in American Wagyu is the cross-breeding strategy. An F1 cross typically pairs a full blood Wagyu sire with an Angus or other breed cow—resulting in 50 % Wagyu genetics and 50 % other breed. Purebred Wagyu means roughly 93.75 % Wagyu genetics. Full blood means 100 % Wagyu genetics, no crossbreeding, a direct trace to Japanese herds. Each step up in genetics tends to increase marbling potential, but the full experience also depends on how the animal is raised.

Terroir and farming style. Another big factor is how the cattle are raised in the U.S. versus Japan. While A5 cattle in Japan might be raised on small family farms with specialized diets, small herds and very high finish levels, American Wagyu ranching often works at larger scale, with more acreage, different feeds, different finishing periods and a more accessible price point. Because of this, the final product is different—not worse, just different. In the U.S., ranchers have to produce more beef to meet domestic demand, which means different size herds, sometimes fewer years to finish, and more range or feedlot variables than a tiny Japanese farm focused only on ultimum marble.

End-use and portion size. Because American steak eaters want a big piece of meat, the market has evolved accordingly. A 16 oz A5 steak may not land the same way in America — for many it would be too rich, overwhelming, and hard to justify. That doesn’t mean a Japanese A5 is “better,” it just means it’s designed for a different experience than American Wagyu. So again: American Wagyu isn’t trying to be A5—it has its own role.

Why This Matters for You

When you walk into a butcher shop, steakhouse or click “buy” online, knowing these differences makes a big difference. If you expect A5 and you get an F1 cross Wagyu, you might be disappointed. Conversely, if you know you’re getting American Wagyu and understand what that means, you’ll enjoy it for what it is: richly marbled, flavorful steak built for the grill.

A lot of great Wagyu doesn’t carry “A5” on it, and that’s completely okay. Because not everyone wants, needs or can afford a tiny ultra-premium portion. American Wagyu offers a real, everyday luxury. And when you understand the distinction—why American Wagyu is different—you’ll not only be a smarter shopper but you’ll actually enjoy it more.